High levels of toxic heavy metals are present in samples taken from the Kingston Fossil Plant ash spill in Harriman, TN, independent testing shows.

High levels of toxic heavy metals are present in samples taken from the Kingston Fossil Plant ash spill in Harriman, TN, independent testing shows.

Preliminary testing was conducted on samples from the Emory River by scientists working in coordination with Appalachian Voices and the Waterkeeper Alliance’s Upper Watauga Riverkeeper Program.

Concentrations of eight toxic chemicals range from twice to 300 times higher than drinking water limits, according to scientists with Appalachian State University who conducted the tests.

“Although these results are preliminary, we want to release them because of the public health concern and because we believe the TVA and EPA aren’t being candid,” said Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., chair of the Waterkeeper Alliance.

The tests were conducted this week at the Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry labs at Appalachian State University in Boone, NC, by Dr. Shea Tuberty, Associate Professor of Biology, and Dr. Carol Babyak, Assistant Professor of Chemistry.

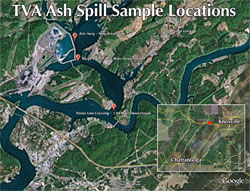

Tuberty and Babyak conducted tests for 17 different heavy metals in triplicate using standard EPA methods. The samples were collected on Saturday, December 27 by Watauga Riverkeeper

Donna Lisenby from three separate locations on the Emory River.

According to the tests, arsenic levels from the Kingston power plant intake canal tested at close to 300 times the allowable amounts in drinking water, while a sample from two miles

downstream still revealed arsenic at approximately 30 times the allowed limits. Lead was present at between twice to 21 times the legal drinking water limits, and thallium levels tested at three to

four times the allowable amounts.

All water samples were found to contain elevated levels of arsenic, barium, cadmium, chromium, lead, mercury, nickel and thallium. The samples were taken from the immediate area of the coal

waste spill, in front of the Kingston Fossil plant intake canal just downstream from the spill site, and at a power line crossing two miles downstream from the spill.

“I have never seen levels of arsenic, lead and copper this high in natural waters,” said Babyak.

A sediment sample was also taken from one of the ash piles at the coal spill site, and revealed even higher levels of heavy metals. Arsenic tested at 135 parts per million, while lead tested at

25 ppm.

Due to the porous topography in the Kingston and Harriman region, well and spring water contamination is one of the primary concerns for nearby populations. “The springs and the well

water in that area need to be closely monitored to see if there is any movement of these arsenic compounds and other heavy metals percolating down through the soil into these wells, because the [surface] levels are 300 times higher,” said Tuberty. “That’s a dangerous level.”

“The highest level of risk you can have with these heavy metals is actually ingesting them,” Tuberty said. “Either drinking or eating them is really the only way it will become an issue, unless you are breathing them. That is coming into play with these ash piles, from drying and becoming picked up from the winds. You can actually breathe them in and that’s the third way you can become exposted to them.”

Recreation on Watts Bar Lake and nearby regions downstream from the site could be affected for some time to come, Tuberty said. Some heavy metals can accumulate in fish, making them unsafe for eating. Although simply touching the water will not necessarily be dangerous for people, failure to wash after contact or swallowing water while swimming could also pose risks.

According to Dr. Tuberty, while the toxicity levels of heavy metals in the water are cause for concern to humans, there is even more cause for concern regarding aquatic life’s ability to survive and reproduce in waters with these levels.

“The ecosystems around Kingston and Harriman are going to be in trouble, the aquatic ones for some time, until nature is able to bury these compounds in the environment,” said Tuberty. “I don’t know how long that will take, maybe generations.”

Of particular concern are metals such as selenium and mercury, which bioaccumulate, or increase in concentrations in tissues of animals higher on the food chain. Birds and mammals that ingest fish and invertebrates contaminated with these metals are at risk of health issues.

The TVA has not released any water quality or solid soil sample results from the immediate spill site. The only results the utility has released to the public to date were from the Kingston water facility intake 6 miles down river from the spill site, and approximately half a mile upstream on the Tennessee River. According to Tuberty, with a sediment spill, downriver contamination can take place over time rather than immediately following a spill.

“There is a huge quantity of this ash still laying there and being picked up from the water,” Tuberty said. “Every time you get a significant rainfall, you’re going to be getting another pulse of this coming through…until [the ash] is removed from the water, and sequestered one way or another, it is going to be a continued input.”

“TVA [and EPA] certainly knows what is in the ash,” Tuberty continued. “[Testing is] part of their routine for solid waste disposal procedures. There is some data out there about how many tons of heavy metals are being released in a year’s time, so they know those numbers.”

“What you could do now is take what was lost to the river, multiply them back by the concentrations of those known compounds in the fly ash, and calculate a likelihood of what number of tons of these different heavy metals have been released in the water.”

“I think it’s going to be a frightening number.”

Dr. Shea Tuberty, an environmental toxicologist at Appalachian State University, earned his doctorate from Tulane University and spent four years conducting EPA post doctoral work at the

University of West Florida.

Dr. Babyak, an environmental chemist at Appalachian State University, obtained her doctorate at West Virginia University and specilized her study on coal plant emissions.

Leave a Reply